Before we go any further, I want to be very clear.

I am not a doctor, registered dietitian, or medical professional. I have been a personal trainer since 2009 and a nutrition coach since 2010, but this article reflects what I personally take and why. It is not medical advice, prescription, or a recommendation that you should do the same.

Supplementation can interact with medications, health conditions, and individual physiology. Before making any changes to your diet, including adding or removing supplements, you should consult with your physician or other qualified healthcare professional to ensure it is appropriate and safe for you.

The Supplements I Take Every Day (And Why I’m Not Here To Hype Them)

Supplement culture is weird.

On one end, you’ve got people treating a basic multivitamin like a magic spell. On the other, you’ve got the “all supplements are a scam” crowd, who act like taking fish oil means you’ve been personally fooled by Big Capsule.

Reality is, as usual, boring. And boring is often where the truth lives.

Supplements are not a substitute for training, sleep, sensible nutrition, stress management, and consistency. They’re not going to give you effortless six-pack abs, and they’re definitely not going to turn you into an elite-level performer while you train three times a week “when life isn’t too busy.” If you’ve followed my work for any length of time, you already know my bias: the fundamentals are the fundamentals because they work, and because you can keep doing them when motivation is gone. (That theme shows up in training too. If you want that parallel, this idea ties closely to what I wrote in Consistency Over Chaos: What Actually Builds Fitness That Lasts: https://www.jpsiou.com/blog/consistency-over-chaos)

So why bother with supplements at all?

Because even when someone eats pretty well, there are still common gaps. North American diets tend to be low in omega-3 fats, many people are short on vitamin D for a big chunk of the year (especially up here), protein is usually under-eaten by active adults, and minerals like magnesium and zinc can be harder to consistently hit than people assume. Add in the reality that training itself is a stressor (a useful one, but still a stressor), and it makes sense that some people look for targeted support.

That’s the lens I use.

The supplements I take daily are mostly about:

Covering common gaps I see in active adults

Supporting performance and recovery in a realistic way

Stacking small advantages that don’t require willpower or perfection

Supporting health as I age, including muscle retention, bone health, immune function, and inflammation management

And just to underline it again: what I do for me is not automatically what you should do for you. Dosage, timing, interactions, medical history, and your actual diet matter.

Here’s what I take daily, and why:

(NOTE: You can click the links in the list below to jump ahead if anything in particular interests you, or just scroll through the whole article to read it all!)

This is the longest article I have yet published, which is one of the reasons I’ve procrastinated on it for so long. Bookmark it so you can read it in chunks and come back to it later if you need to!

Protein Powder (and protein in general)

Protein is not a supplement topic in the way people usually think, but it shows up in supplement conversations because protein powder is one of the easiest “bridges” between knowing what you should eat and actually doing it consistently.

At a basic level, dietary protein supplies essential amino acids that support muscle protein synthesis (MPS), connective tissue and bone through collagen and structural proteins, and immune and enzyme function. When people talk about protein for muscle, the key mechanism that comes up is activation of the mTOR pathway, driven by essential amino acids (particularly leucine) when enough protein is consumed per meal and per day. In practical terms, it’s less about one magical shake and more about consistently hitting a meaningful daily intake, distributed across meals.

For generally active adults and athletes, position statements and reviews commonly land in the ballpark of roughly 1.2–2.2 g/kg/day, with higher intakes within that range often used during heavy training or fat loss phases. Those intakes are above the standard 0.8 g/kg/day reference intake that’s often quoted for the general population, because that general reference is not written for people training hard, trying to build or retain muscle, or trying to manage hunger during a calorie deficit. Instead, it’s simply what’s needed to prevent protein deficiency in the average, sedentary person.

This is also where I’ll add my own “coach reality” layer, because people ask me this constantly.

With clients, I typically use:

A baseline of about 0.74 grams per pound / 1.6 grams per kg of body weight (which tends to work out to roughly 4–6 palm-sized portions per day for many people), and

Up to about 1 gram per pound / 2.2 g per kg of body weight (6–8 palm-sized portions) when someone needs it to support heavier training, improve recovery, or manage hunger more effectively.

Protein powders, whether whey, casein, soy, pea, rice, or blended plant sources, are simply tools to make that execution easier. They help people reach total daily targets and deliver convenient per-meal doses around 0.25–0.40 g/kg, spread across the day. Whey gets a lot of attention because it digests quickly and has a high leucine content, which makes it strong for acutely increasing MPS. Casein digests more slowly, which can support sustained amino acid availability overnight, and some research links pre-sleep casein with modest overnight MPS benefits.

Plant proteins deserve a fair shake here too, because they’re not “second class” in the way old gym lore sometimes makes them out to be. Soy and other plant proteins (pea, rice, blended options) can support strength and muscle gain when total protein and leucine intake are matched, even though some plant proteins have slightly lower digestibility or a less optimal essential amino acid profile. In practice, that can mean slightly higher doses, better blends, or just more consistency across the day. Some evidence in older adults even links plant protein intake with lower prevalence of sarcopenia, which is a useful reminder that the bigger picture matters: total intake, dietary pattern, training, and overall health behaviours.

Beyond muscle and performance, adequate protein supports healthy aging by helping preserve muscle and function, especially when paired with resistance training and sufficient energy intake. Higher protein diets can also improve satiety and support weight management, which indirectly helps cardiometabolic health and inflammation through improved body composition and metabolic function. The evidence is weaker for direct effects of protein powders on inflammation, cardiovascular risk, or cognition. If those benefits happen, they’re likely indirect, via better training quality, better recovery, better body composition, and better physical function, not because protein powder itself has some unique anti-inflammatory superpower.

So the question I come back to is simple: it’s not “do you need protein powder?” It’s “do you need protein powder to consistently hit an evidence-based daily protein target without making your life harder than it needs to be?”

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Supports MPS, strength, and hypertrophy when combined with resistance training; helps preserve lean mass during energy restriction and aging; aids satiety and weight management.

Performance effects: Higher protein intakes (≈1.2–2.0 g/kg/day) support training adaptations in endurance and strength athletes; timing around sessions and at regular meals may modestly enhance recovery and muscle gains.

Inflammation/recovery: Indirect benefits through better repair and maintenance of lean tissue; no strong evidence that protein powder per se has anti-inflammatory effects beyond meeting needs.

Age/longevity: Adequate protein is linked to reduced sarcopenia risk and better physical function in older adults, which is relevant to healthy aging and independence.

Safety/contraindications: Intakes up to at least 2.2 g/kg/day appear safe in healthy adults with normal renal function; those with kidney disease or specific metabolic disorders should follow medical advice.

Why And How I Use It

I use protein powder primarily to help preserve lean muscle mass and support tissue turnover and repair with the amount of training I’m doing.

This isn’t just a bodybuilder or strength athlete thing either. In endurance sports especially, people tend to focus heavily on replenishing energy stores with carbs or other fuel, and often neglect the fact that endurance work causes huge amounts of tissue damage. If you’re logging a lot of mileage (or piling on a ton of volume in the gym), protein isn’t just about “gains”, it’s about giving your body the raw materials to actually rebuild what you’re breaking down.

I’m also not someone who struggles to eat a high volume of food. In this case, it’s a blessing (even if it’s often a curse in other contexts). Most days I can meet my baseline protein needs (around 136 grams) through food alone, between the Greek yogurt I have at breakfast and assorted lean meats, poultry and seafood throughout the rest of my day.

But that baseline doesn’t always account for the higher workloads I put my body under. I want a buffer in place so I’m not consistently short-changing recovery, or leaning too hard on my body’s ability to rob Peter to pay Paul (breaking down lean tissue to repair other tissue). That’s where protein powder comes in for me. It’s less about replacing food, and more about making sure the numbers stay solid when training volume climbs.

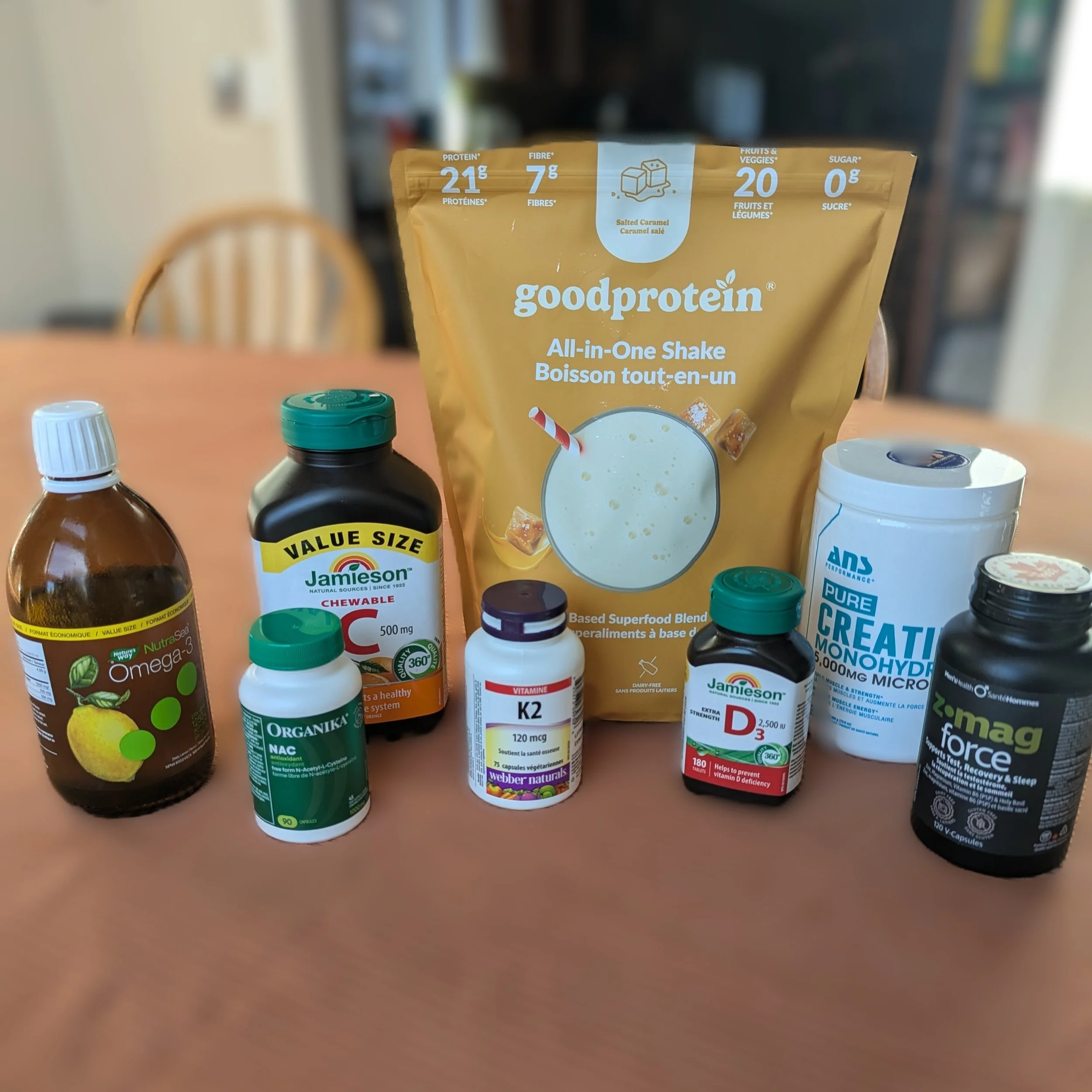

One more practical wrinkle: I don’t do great with whey or other dairy-based protein powders if I use them for too long. Thanks, Asian genes… LOL. So I use a plant-based protein powder from Good Protein.

My usual routine looks like this:

Morning: I mix 22 grams (about half a heaped scoop) into my yogurt bowl to bump the protein content up by roughly 10 grams.

Evening: I’ll have another 44–66 grams mixed with water in a shaker cup for another 20-30 grams of protein, usually while I’m running client training sessions or after I’m done for the day.

And because I can’t leave well enough alone, I’ve also been experimenting with using the protein powder to make “ice cream” in the Ninja Creami. The best results so far have come from using a double-concentration of powder to liquid, plus a couple of small tweaks to enhance flavour. It’s not perfect, but it’s been surprisingly solid for something that’s still basically a protein hack.

Creatine

Creatine is one of the few supplements that I’d put in the “boringly effective” category. It’s not new. It’s not flashy. It’s not dependent on marketing gimmicks. It just tends to work, particularly if you do the thing that actually makes it matter: train.

Creatine monohydrate increases intramuscular phosphocreatine stores, which helps your body regenerate ATP more quickly during short, high-intensity efforts. That’s the phosphagen system doing what it does best: supporting repeated high-output work like heavy sets, sprints, and power efforts. In practical training terms, this often shows up as slightly better performance on repeated sets, slightly more total training volume over time, and better strength and hypertrophy outcomes when paired with resistance training.

Mechanistically, creatine’s main role is the energy-buffering piece, but it may also have secondary effects related to cell hydration, anabolic signalling, and satellite cell activity. In the real world, you don’t need to obsess over those details. What matters is that large meta-analyses consistently show improved maximal strength when creatine is combined with resistance training, with effects seen in both trained and untrained people, often stronger in untrained participants. A 2025 meta-analysis also found significant improvements in muscle strength across age groups, with better results at standard dosing rather than very high doses.

Creatine also has a decent body of research on muscle size. A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis looking at trials using direct measures of muscle size found a small but consistent hypertrophy benefit when creatine is paired with resistance training. It’s not a steroid. It’s not going to override poor training. But it can slightly tilt the odds in your favour over time, which is the whole point of sensible supplementation.

Where creatine gets interesting for healthy aging is the sarcopenia angle. In older adults, creatine plus resistance training generally produces greater gains in lean mass and strength compared with training alone, although effect sizes can be smaller than in younger adults and responses vary. Still, if your long-term goal is maintaining muscle and function as you age, and you’re already doing resistance training, creatine is one of the more evidence-backed options to consider, with appropriate medical context.

Endurance is more nuanced. Creatine isn’t a classic endurance supplement. Benefits are less robust, but it may still help with repeated high-intensity efforts within endurance sports, like hills, surges, sprint finishes, or mixed-modality demands. The trade-off is that creatine can increase body mass, which is not always desirable depending on the sport, the athlete, and the context.

There’s also a growing research thread around creatine and neuroprotection, mood disorders, and cognitive decline, given its role in brain energy metabolism. That evidence is promising in certain clinical contexts, but in healthy adults it’s limited and mixed, so I treat it as exploratory rather than a selling point.

On safety, long-term data in healthy adults are generally reassuring, with no clear evidence of kidney damage in people without pre-existing renal disease. Standard protocols (3–5 g/day, with or without a loading phase) are widely used.

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Increases intramuscular phosphocreatine, enhancing short-duration, high-intensity performance and strength gains; augments resistance-training-induced muscle hypertrophy.

Performance effects: Improves 1RM strength, repeated sprint ability, and power output in many sports; effects are strongest in high-intensity, intermittent efforts.

Inflammation/recovery: May modestly reduce markers of muscle damage and improve recovery in some studies, but this is secondary to its primary energy-buffering role.

Age/longevity: In older adults, creatine plus resistance training supports better gains in lean mass and strength, potentially helping mitigate sarcopenia; neuroprotective and cognitive benefits are promising but not yet conclusive.

Safety/contraindications: Generally well tolerated at 3–5 g/day; common issues are transient water weight gain and occasional GI upset at higher doses. Those with kidney disease or on nephrotoxic medications should seek medical advice before use.

Why And How I Use It

On the physical performance side, I use creatine primarily for its ability to improve intra-workout recovery through enhanced ATP regeneration.

That matters in obvious ways during higher-intensity training like intervals, hill repeats, tempo efforts, or heavier strength work. But it also matters in less obvious ways during longer endurance sessions. Even in predominantly aerobic work, there are still brief bursts of higher output, short climbs, surges, accelerations, technical sections, finishing kicks. Having a slightly more robust phosphocreatine system can support those efforts and improve how well I bounce back between them.

There’s also emerging evidence around creatine’s potential role in increasing muscle glycogen storage and possibly moderating exercise-induced inflammation. Neither of those are magic bullets, but both are interesting from a training density and recovery standpoint. When you’re stacking sessions week after week, small advantages add up.

That said, the physical performance side is not actually my primary driver.

What really interests me about creatine is its role in brain energy metabolism.

Creatine is involved in cellular energy buffering in the brain just as it is in muscle. There’s growing research around its potential relevance for mood disorders, cognitive decline, and neuroprotection. The evidence isn’t conclusive across the board, but it’s compelling enough to pay attention to.

Having dealt with medically diagnosed depression periodically throughout my life, and having experienced some troubling neurological symptoms over the past several years without a clear diagnosis, this is the piece that carries the most weight for me. If there is even a reasonable chance that creatine can support brain energy metabolism and resilience over time, that’s worth the daily scoop.

In terms of what I actually use, I keep it simple.

I use plain creatine monohydrate powder from reputable brands, usually whatever is least expensive when I need to restock. There’s no need for fancy delivery systems or proprietary blends. Creatine monohydrate is the form with the most research behind it.

For a long time, I was taking 5 grams daily, mixed into my protein powder and water.

More recently, some findings have suggested that a higher daily dosage, around 0.1 grams per kilogram of body mass, may be more appropriate to fully saturate tissue stores and potentially support the broader spectrum of benefits, including neurological applications. Based on that, I’ve increased my intake to 10 grams daily.

I split that into:

5 grams mixed into my yogurt bowl in the morning, and

5 grams mixed in with my protein powder and water in the evening.

Some people report GI distress when taking higher single doses, so spreading it out makes sense for me. It’s been about two months on that increased dosage, and so far, so good.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA And DHA)

Omega-3s are one of the more “health-first” supplements I take, but they still have relevance for performance, recovery, and aging. The short version is that EPA and DHA are long-chain omega-3 fatty acids found primarily in fish and fish oil, and they play structural and signalling roles in cell membranes, including in the brain, retina, muscle, and immune tissues.

Mechanistically, omega-3s are incorporated into cell membranes and can shift inflammatory signalling by altering eicosanoid and specialised pro-resolving mediator pathways. That’s a fancy way of saying they can influence how the body handles inflammation and recovery, which matters in both general health and training. They also lower triglycerides in a well-established way, and they have a strong evidence base for certain cardiovascular benefits, particularly in specific populations and dosing contexts.

For athletic performance and muscle health, omega-3s are not “pre-workout fuel,” but they may support muscle protein synthesis sensitivity and recovery in some contexts, especially in older adults. Some studies suggest omega-3s may support muscle function and preserve lean mass as people age, potentially relevant for sarcopenia prevention, though evidence is mixed and outcomes vary based on population, dose, and study design.

For inflammation and joint discomfort, omega-3s are commonly used because of their role in inflammatory modulation. The evidence is stronger in certain inflammatory conditions and less definitive for general “training inflammation,” but many people use them as part of a broader health-support routine.

On cognitive and neuroprotective benefits, DHA is a structural component of brain tissue, and omega-3 status has been linked with cognitive health markers in observational studies. Intervention trials vary, and outcomes are inconsistent depending on baseline status, age, and cognitive state. In other words, it’s a reasonable area of interest, but I wouldn’t treat it as a guaranteed brain upgrade.

Omega-3s also come with important nuance around cardiovascular outcomes and safety. Large trials show benefits in some contexts, but there’s also evidence of increased risk of atrial fibrillation with higher-dose omega-3 supplementation in some studies. That doesn’t mean “never take fish oil,” but it does mean this is not a harmless, no-context supplement, especially if someone has arrhythmia risk factors or a history of heart rhythm issues. Medical context matters.

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Lowers triglycerides; supports cardiovascular health in select populations; contributes to anti-inflammatory signalling and membrane structure.

Performance effects: Evidence for direct performance enhancement is limited; may support recovery and muscle function in some contexts, particularly in older adults.

Inflammation/recovery: Can reduce inflammatory markers and may benefit joint discomfort; effects vary by dose and baseline omega-3 status.

Age/longevity: Potential role in preserving muscle function and cognitive health with aging, though evidence is mixed and population dependent.

Safety/contraindications: Generally safe at common doses; higher doses may increase bleeding risk and have been associated with higher atrial fibrillation risk in some trials. Use caution with anticoagulants or arrhythmia history and seek medical advice.

Why And How I Use It

I take omega-3s mostly for their effect on chronic inflammation and on improving the overall omega-3 to omega-6 ratio in my diet.

In an ideal world, you could improve that ratio purely through food. That would mean prioritising grass-fed, free-range meat and poultry, eating wild-caught oily fish regularly, and keeping grain-heavy processed foods to a minimum. In reality, doing that consistently at a meaningful dose is expensive, inconvenient, and hard to sustain. High-quality fish oil is simply a more practical and cost-effective way for me to move the needle.

And for me, this isn’t theoretical.

My body is very prone to inflammation. I’ve dealt with gout since I was 30, so over two decades now. I’ve had other creaky, inflamed joints. I have some skin issues that my dermatologist attributes to inflammatory processes. I deal with chronic sinusitis, which is literally inflammation of the sinuses, and environmental allergies layered on top of that.

So when I look at omega-3s, I’m not looking at them as a trendy add-on. I’m looking at them as part of a broader inflammation-management strategy.

Beyond inflammation, I’m also interested in their effect on cell membrane structure and permeability. EPA and DHA become incorporated into cell membranes, influencing membrane fluidity and signalling pathways. In practical terms, that affects how efficiently nutrients move into cells and how waste products move out. That’s not flashy, but it’s foundational physiology.

There’s also the cardiovascular piece, and this is where things get serious for me.

I have familial hypercholesterolemia, meaning my cholesterol is genetically elevated. On top of that, I have elevated lipoprotein(a), and that combination is considered such a significant risk factor that the physician at the lipids clinic told me I essentially need to operate as though I’ve already had a heart attack.

So in addition to the daily medications I take, I’m doing everything I reasonably can from a lifestyle and nutrition standpoint to support my lipid profile. Omega-3s can help lower triglycerides and may positively influence certain serum lipid markers. They are not a replacement for medication in my case, but they are part of the overall strategy.

In terms of what I use, I take 1 tablespoon daily of NutraSea Omega-3 lemon-flavoured liquid, which provides approximately 3.75 grams of EPA and 1.5 grams of DHA per day.

I’ve experimented with different ways of taking it.

I used to mix it into my protein powder and water. That worked… until I forgot to properly wash my shaker cup. Rinsing is not enough. If you let it sit, you will know. Even though the oil itself doesn’t taste fishy and has a pronounced lemon flavour, the residual smell is not something you want lingering in your gear.

Then I went through a phase of taking it straight off the tablespoon and chasing it with water. That worked functionally, but it was just kind of… yucky. I eventually fell off consistency because of that.

The breakthrough was mixing it into my morning yogurt bowl.

Adding the fat to fat-free yogurt makes it noticeably creamier (duh), which is already a win. But the lemon flavour combined with my Chai Latte Good Protein powder and blueberries is genuinely excellent. It’s not a chore. I actually look forward to it every single morning.

For me, that’s the key. If something is theoretically beneficial but practically annoying, I won’t stick with it. This setup is sustainable. And sustainability is what actually matters.

Vitamin D3

Vitamin D is one of those nutrients that gets talked about like it’s purely a “bone vitamin,” but it’s involved in a lot more than that. Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is either produced in the skin with UVB exposure or obtained through diet and supplements, and it’s converted into active forms that influence calcium and phosphate balance, bone metabolism, and a wide range of gene regulation pathways.

For skeletal health, vitamin D helps support calcium absorption and bone mineralisation. Deficiency is associated with osteomalacia in adults and contributes to osteoporosis risk when paired with other factors. From a training and aging perspective, maintaining adequate vitamin D status matters because bone integrity and muscle function are not optional if you want to keep doing hard things over the long haul.

Vitamin D also has a relationship with muscle function. Vitamin D receptors exist in muscle tissue, and deficiency has been associated with muscle weakness and higher fall risk in older adults. Supplementation tends to show clearer benefits when baseline vitamin D status is low. If someone already has adequate levels, “more” does not automatically mean “better,” and that’s where supplementation needs to be viewed through a lab-and-context lens rather than a hype lens.

Immune function is another big reason people take vitamin D. Vitamin D influences innate and adaptive immune responses, and lower vitamin D status has been linked with increased risk of respiratory infections in observational research. Supplementation trials show mixed results overall, but meta-analyses suggest that vitamin D supplementation may reduce risk of acute respiratory infections, particularly in those who are deficient or insufficient at baseline, and with appropriate dosing patterns.

For cardiovascular and cognitive benefits, evidence is mixed. Vitamin D deficiency correlates with a lot of negative health outcomes, but correlation is not the same as causation, and intervention trials often fail to show dramatic benefits in already-healthy populations. That doesn’t mean vitamin D is useless, it just means it’s not a cure-all.

Vitamin D also has a clear safety consideration: it’s fat-soluble, and excessive dosing can lead to toxicity, hypercalcaemia, and related complications. This is one of the supplements where “check your levels” is not a bureaucratic annoyance, it’s the smart move.

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Supports calcium absorption and bone mineralisation; reduces risk of deficiency-related bone disease; may improve muscle function in deficient individuals.

Performance effects: Mixed evidence for performance gains; benefits are most likely when correcting deficiency, which may improve strength and reduce injury risk indirectly.

Inflammation/recovery: Vitamin D has immunomodulatory roles; direct anti-inflammatory effects in healthy athletes are not consistently demonstrated.

Age/longevity: Adequate vitamin D status supports bone health and may reduce falls in older adults, especially when combined with calcium in certain populations.

Safety/contraindications: Excess supplementation can cause hypercalcaemia and toxicity; dosing should be guided by baseline levels and medical advice, especially in those with kidney disease or granulomatous disorders.

Why And How I Use It

I take vitamin D because, realistically, it only makes sense.

I live in Canada. I spend a good chunk of my time indoors coaching, writing, programming, and doing the normal day-to-day things that don’t involve standing shirtless in midday sun for optimal UVB exposure. Even when I am outside training, it’s not always at the right time of day, and it’s not always in the right season to meaningfully support vitamin D production.

On top of that, I don’t drink milk. I don’t eat processed cereals. I don’t eat commercial breads. Those are three of the most common fortified sources of vitamin D in the general population, and they’re simply not part of my diet. So even if someone argues that fortification “covers the gap” for most people, that coverage doesn’t apply to me in the same way.

I keep meaning to get my levels tested to confirm where I actually sit, and at some point I probably will. But when I look at the broader context, this feels like a very low-risk, high-likelihood gap to address. A large proportion of the population is either deficient or on the very low end of normal, especially in northern latitudes. At the dose I use, toxicity risk is low for healthy individuals. It’s inexpensive. It’s easy to take. And the upside, if I am running low, is meaningful.

The benefit I care most about is bone health.

Vitamin D plays a central role in calcium absorption and bone mineralisation. I don’t drink milk at all, and while I do eat yogurt almost every day, I don’t take a separate calcium supplement. From a long-term perspective, especially as I age, I want to stack the deck in favour of maintaining bone density. Resistance training helps. Adequate protein helps. But vitamin D is part of that ecosystem. Taking it helps put my mind a bit more at ease that I’m not leaving a basic variable unaddressed.

The potential immune system benefits are interesting too. With my chronic allergies and sinus issues, anything that supports immune regulation is worth paying attention to. That said, this is secondary for me. I’m not taking vitamin D as an immune “hack.” I’m taking it primarily as structural insurance for bone health, with immune support as a possible bonus.

In terms of what I use, I take 5,000 IU daily, either in tablet or gel cap format, whichever is cheapest and available when I restock. Absorption differences between formats are minimal in real-world use, especially when taken with food, so I don’t overthink the delivery system.

I take the full dose in the morning with my daily medications. That makes it convenient, which means I actually remember to take it. There’s also some research suggesting potential advantages to taking vitamin D earlier in the day rather than at night, so morning dosing works well on both the practical and theoretical fronts.

For me, vitamin D isn’t flashy. It’s foundational. And sometimes that’s exactly the point.

Vitamin K2

Vitamin K is often lumped into the “blood clotting” category, and that’s true, but vitamin K2 has an additional conversation attached to it because of its role in directing calcium to the right places.

Vitamin K2 refers to a group of menaquinones (like MK-4 and MK-7) that act as cofactors for enzymes involved in activating vitamin K-dependent proteins. Two that come up frequently are osteocalcin (in bone) and matrix Gla protein (in blood vessels). The simplistic version people repeat is: K2 helps activate proteins that support bone mineralisation and may reduce vascular calcification risk by helping regulate calcium deposition.

The evidence base is interesting but not universally conclusive, and it varies depending on the form of K2, the population being studied, baseline dietary intake, and whether vitamin D status and calcium intake are also considered. In other words, it’s not a “one pill solves bone health” situation, but it may be a useful support layer in the right context.

For bone health, some trials suggest K2 supplementation may reduce fracture risk or support bone mineral density in certain populations, particularly in older adults or those at higher risk. Other studies show less dramatic effects. This is one of those supplements where I think it makes sense to treat it as potentially supportive, especially when paired with resistance training, adequate protein intake, and appropriate vitamin D status, rather than treating it as a standalone solution.

For cardiovascular health, the vascular calcification angle is why people pay attention. Observational studies have linked higher dietary K2 intake with lower cardiovascular disease risk, and mechanistic plausibility exists through matrix Gla protein activation. Intervention evidence is still emerging and mixed, so again, useful to treat with measured optimism rather than certainty.

There are also important contraindications here: vitamin K interacts with anticoagulant medications (especially warfarin). Anyone on blood thinners should not casually add vitamin K supplementation without medical oversight. That’s not optional.

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Activates vitamin K-dependent proteins involved in bone metabolism; may support bone mineral density and reduce fracture risk in select populations.

Performance effects: No strong evidence for direct performance enhancement; potential benefits are indirect via skeletal health.

Inflammation/recovery: Limited evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects; relevance is mainly through bone and vascular pathways.

Age/longevity: Observational links between higher K2 intake and lower cardiovascular risk; potential role in reducing vascular calcification remains under investigation.

Safety/contraindications: Can interfere with anticoagulant therapy (e.g., warfarin); anyone on blood thinners should seek medical guidance before supplementation.

Why And How I Use It

Vitamin K2 is very simple for me.

I take it because of how it complements vitamin D.

Vitamin D helps increase calcium absorption. That’s one of the main reasons I take it in the first place, to support bone health and mineralisation as I age. But increasing calcium absorption is only part of the story. What matters just as much is where that calcium ends up.

Vitamin K2 plays a role in activating proteins like osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein, which are involved in directing calcium toward bone tissue and away from soft tissues like blood vessels. In practical terms, I think of K2 as helping “aim” the calcium that vitamin D helps absorb.

Given my cardiovascular risk profile, that distinction matters to me.

With familial hypercholesterolemia and elevated lipoprotein(a), I already operate under the assumption that I need to be proactive about vascular health. The last thing I want is to increase calcium absorption without also supporting the mechanisms that help regulate where that calcium is deposited. While the evidence is still evolving, the potential role of K2 in reducing vascular calcification risk makes enough physiological sense that it feels like a reasonable safeguard alongside vitamin D.

This isn’t about megadosing or chasing fringe theories. It’s simply about pairing nutrients in a way that respects how they interact in the body.

I take one 120 mcg capsule daily, alongside my vitamin D in the morning. Same time, same routine, no overcomplication. It keeps the habit simple, and that’s what makes it sustainable.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C is one of those supplements that people either dismiss as useless or treat like a force field. The truth is more practical than either extreme.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is a water-soluble vitamin with antioxidant roles and essential cofactor functions for enzymes involved in collagen synthesis, catecholamine production, and gene-regulating hydroxylation reactions. Collagen is the obvious connective tissue headline, but vitamin C’s influence on immune function and oxidative stress is also a big part of why it gets so much attention.

From an immune standpoint, vitamin C supports epithelial barrier integrity and helps with immune cell function, including chemotaxis and phagocytosis in neutrophils, and it can influence lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production. Vitamin C levels can drop during infections and physiological stress, which suggests requirements may increase in those states. That doesn’t automatically mean mega-dosing is the answer, but it does support the idea that vitamin C is not irrelevant when the body is under heavier demand.

When you look at supplementation research in generally healthy adults, randomized trials and meta-analyses often show modest outcomes. Vitamin C doesn’t consistently prevent colds in the general population, but it may slightly reduce cold duration and severity, and benefits appear more pronounced in people under heavy physical stress (such as endurance athletes, soldiers, or those in cold environments). That lines up with the “stress increases demand” concept, and it’s one reason vitamin C stays in the conversation for active people.

On exercise performance, vitamin C is not consistently ergogenic, and there’s nuance that often gets lost: because vitamin C is an antioxidant, high-dose antioxidant supplementation has been studied for whether it could blunt some training adaptations by reducing the signalling role of exercise-induced oxidative stress. Evidence is mixed, and the practical takeaway is not “never take vitamin C,” it’s “don’t assume that more is always better, especially if you’re trying to drive adaptation.”

Vitamin C’s role in collagen synthesis is also relevant for connective tissue health, wound healing, and general structural maintenance. That matters for athletes and aging adults, because tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and vascular tissues all live in the “structure” category. You can’t train hard for long if your structure is constantly irritated and under-repaired.

Inflammation is similar: vitamin C can modulate oxidative stress and inflammatory signalling, but the real-world effect depends heavily on baseline status. If someone is already getting adequate vitamin C through diet, adding a supplement may not do much. If someone’s intake is poor, supplementation may correct deficiency and support normal function, which is a very different outcome.

For cardiovascular and cognitive outcomes, evidence is not consistently strong in intervention trials, even though observational studies often link higher vitamin C intake with better health outcomes. Again, correlation is not causation, and dietary patterns matter. Vitamin C might be acting as a marker for fruit and vegetable intake, which brings a whole package of benefits.

Safety-wise, vitamin C is generally well tolerated at common doses, but higher doses can cause GI upset and may increase risk of kidney stones in susceptible individuals. That’s another reason I keep the “medical context matters” disclaimer front and centre.

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Essential for collagen synthesis, antioxidant defense, and immune cell function; prevents scurvy and corrects deficiency.

Performance effects: Does not reliably enhance athletic performance; may reduce cold incidence in people under extreme physical stress (e.g., endurance athletes) and slightly shorten cold duration.

Inflammation/recovery: Can reduce oxidative stress and may modestly lower inflammatory markers in some studies, but effects depend on baseline status and dose.

Age/longevity: Higher dietary vitamin C intake is associated with better health outcomes in observational studies, but supplementation benefits in well-nourished adults are inconsistent.

Safety/contraindications: Generally safe at common doses; high doses can cause GI upset and may increase kidney stone risk in susceptible individuals.

Why And How I Use It

Vitamin C, for me, is mostly about connective tissue.

I take it primarily for its role in collagen synthesis. With the amount of training stress I put on my body, especially through running and strength work, I want to give my joints, tendons, ligaments, and connective tissues the raw materials they need to repair and remodel effectively. Collagen turnover isn’t just a cosmetic thing. It’s structural. If you’re going to keep loading tissue year after year, you need that structure to stay resilient.

The immune piece is secondary but still relevant.

My body tends to live in a fairly high-stress environment. High training loads, chronic allergies, sinus inflammation, work stress, normal life stress. Vitamin C’s modest immune-support benefits are interesting in that context. I’m not expecting it to prevent illness outright, but if it can slightly reduce duration or severity when the system is under load, that’s a reasonable return on a very low-cost supplement.

The antioxidant angle is where I’m a bit more cautious.

Vitamin C does have general antioxidant properties, and from a recovery standpoint that’s appealing. But I’m also aware of the research suggesting that high-dose antioxidant supplementation may blunt some training adaptations by dampening the signalling role of exercise-induced oxidative stress. I don’t want to accidentally undermine the very adaptations I’m training for. So for me, this is about moderation, not megadosing.

Right now, I take two 500 mg chewable tablets in the morning, after all my other medications and supplements. It’s simple, and it’s consistent.

I have considered splitting the dose, taking 500 mg in the morning and 500 mg in the afternoon, since that could theoretically improve absorption given vitamin C’s water-soluble nature. More likely than not, what that will actually do is result in me taking the 500 mg in the morning and forgetting the afternoon dose entirely.

So for now, consistency wins.

ZMA (Zinc, Magnesium, Vitamin B6)

ZMA is one of those supplements that sits right at the intersection of marketing and legitimate nutrition. Zinc, magnesium, and vitamin B6 are all real nutrients with real physiological roles. The question is whether combining them into one branded product produces meaningful outcomes beyond correcting deficiencies, and whether the “testosterone and gains” hype holds up.

ZMA combines zinc, magnesium (often aspartate), and vitamin B6, and it’s marketed for testosterone support, recovery, sleep quality, and muscle gains. Mechanistically, zinc is involved in hundreds of enzymatic reactions, hormone synthesis (including testosterone), and immune function. Magnesium participates in energy metabolism, neuromuscular function, and pathways involved in sleep regulation. Vitamin B6 acts as a cofactor in amino acid metabolism and neurotransmitter synthesis.

So yes, in theory, correcting deficiencies could improve fatigue, immune function, sleep quality, and general performance readiness. Athletes may be at risk of lower zinc and magnesium status due to sweat losses and high training loads, and poor intake is more common than people assume.

But this is where ZMA’s claims run into the wall of controlled research.

Controlled trials of ZMA in resistance-trained men have not supported strong ergogenic claims. One well-designed 8-week randomised, double-blind trial found that ZMA supplementation did not significantly change anabolic or catabolic hormone profiles, body composition, maximal strength, muscular endurance, or anaerobic capacity compared with placebo in trained males. That finding matters because it directly challenges the earlier, less rigorous claims that ZMA meaningfully boosts testosterone and strength in already well-nourished, resistance-trained populations.

Where ZMA may still be relevant is in more practical areas:

People who are low in magnesium or zinc

People whose sleep quality might improve when magnesium status improves

People who aren’t eating well consistently, especially under high stress

People who struggle with cramps, restless sleep, or general recovery quality

That’s not a guarantee, and it’s not a licence to ignore the basics, but it’s a more realistic use case than “ZMA will raise your testosterone and change your physique.”

Another important nuance is that supplement forms and doses matter, and interactions matter. High zinc intake can interfere with copper absorption. Magnesium can cause GI upset depending on the form and dose. And if someone is already getting adequate amounts through diet and a multivitamin, piling more on top isn’t automatically beneficial.

So if ZMA is on your radar, the more evidence-aligned question is not “will it boost testosterone,” but “am I likely low in any of these, and would correcting that improve sleep, recovery, or general readiness?”

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Correcting zinc or magnesium deficiency can improve sleep quality, immune function, and general recovery; B6 supports amino acid and neurotransmitter metabolism.

Performance effects: In resistance-trained men, ZMA has not shown significant improvements in strength, endurance, or body composition when baseline nutrition is adequate.

Inflammation/recovery: Magnesium and zinc support normal immune and inflammatory regulation; supplementation benefits are most apparent in deficient individuals.

Age/longevity: Adequate magnesium and zinc status supports metabolic health, immune resilience, and sleep quality, which are relevant to healthy aging; direct longevity claims are unproven.

Safety/contraindications: High zinc intake can impair copper absorption; excessive magnesium may cause GI distress. Individuals on medications or with medical conditions should consult a clinician.

Why And How I Use It

I take ZMA mostly for its effect on sleep quality.

I am a terribly restless sleeper. I wake up and turn over frequently throughout the night. That part hasn’t magically disappeared. But what used to happen was worse. I would wake up fully, sometimes several times a night, and then lie there wide awake, struggling to fall back asleep.

Since taking ZMA consistently, that pattern has changed.

I still wake and shift positions a lot, but I fall back asleep almost immediately. That alone has made a significant difference. The total amount of sleep I get, and more importantly the quality of it, is light years better than it used to be. I’m not tracking sleep stages obsessively. I’m judging by how I feel, how quickly I recover, and how consistent my energy is day to day. By those measures, it’s been a meaningful improvement.

The second reason I started paying attention to magnesium was cramping.

I used to get calf cramps fairly frequently, both during the night and occasionally during activity. Night cramps can sometimes be associated with magnesium deficiency, though not always. Since taking ZMA regularly, I honestly can’t remember the last time I had a calf cramp wake me up in the middle of the night. Cramping during activity has decreased as well.

That said, I’m careful not to attribute everything to a capsule.

A big part of the reduction in activity-related cramping is likely due to improved training, better pacing, and simply becoming more experienced with endurance work. I’m better at not overreaching early in sessions, and my conditioning is better overall. Still, the change in night-time cramping, in particular, was noticeable after adding ZMA consistently.

For me, this one is less about hormones or strength gains and more about sleep and recovery quality. If I sleep better, everything else works better. That alone makes it worthwhile in my routine.

I take the recommended dosage about an hour before bedtime every night.

N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

NAC is the newest addition to my daily stack, and it’s also the one I’m the most careful about discussing, because it’s easy for NAC conversations to slide into “this fixes everything” territory. It doesn’t. But it is genuinely interesting, and it has legitimate research behind it in specific contexts.

N-acetylcysteine is a precursor to cysteine, which is a building block for glutathione synthesis. Glutathione is one of the body’s key endogenous antioxidants, and it plays a major role in managing oxidative stress and maintaining redox balance. NAC can also act as a mucolytic, meaning it can help thin mucus by breaking disulfide bonds in mucoproteins. That’s part of why NAC has been used in respiratory contexts for a long time.

In the athletic performance world, NAC has been studied for whether boosting antioxidant capacity might reduce fatigue, improve endurance, or support recovery. The evidence is mixed. Some studies suggest NAC can delay fatigue in certain high-intensity or endurance contexts, likely related to oxidative stress and muscle fatigue mechanisms, but outcomes vary depending on dose, timing, training status, and the exact performance test used. And as with other antioxidant-related supplements, there’s a recurring nuance: reducing oxidative stress is not always purely beneficial if it interferes with the signalling that drives training adaptation. The evidence isn’t definitive, but it’s enough that I’m cautious about framing NAC as a general performance enhancer.

Where NAC has stronger footing is in clinical and respiratory contexts. It’s used as a mucolytic in chronic bronchitis and COPD, and research continues to explore its role in airway inflammation and symptom management. There are trials where high-dose oral NAC does not improve respiratory health status in severe COPD, and others looking at airway inflammation and quality of life in bronchiectasis, including more recent work. That doesn’t mean “it works” or “it doesn’t,” it means the effect depends on context, severity, and study design.

NAC is also used in medical settings for acetaminophen overdose because it helps replenish glutathione and protect the liver. That’s a completely different use case than daily supplementation, but it’s part of why NAC is taken seriously as a compound with meaningful physiological effects.

For inflammation and neuroprotection, NAC is being studied in a range of clinical contexts, including psychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative conditions, because oxidative stress and glutathione pathways are implicated in those conditions. Evidence is still emerging, and in healthy adults it’s not a slam dunk. Promising, interesting, not guaranteed.

Safety-wise, NAC is generally well tolerated, but GI upset can occur, and there can be interactions or concerns for people with certain medical conditions or medications. This is one of the supplements where I really do mean it when I say: talk to your medical professional first.

Main Highlights

Most evidence-supported benefits: Precursor to glutathione, supporting antioxidant defense; established mucolytic use in respiratory conditions; clinically used in acetaminophen toxicity.

Performance effects: Mixed evidence for delaying fatigue in endurance or high-intensity exercise; outcomes depend on dosing, timing, and study design.

Inflammation/recovery: May reduce oxidative stress and modulate inflammatory pathways; relevance in healthy athletes is not consistently demonstrated.

Age/longevity: Investigated for neuroprotective and psychiatric applications through redox pathways; evidence in healthy aging remains limited.

Safety/contraindications: Generally well tolerated; possible GI side effects and interactions. Medical guidance advised for those with chronic disease, asthma, or on medications.

Why And How I Use It

NAC wasn’t originally on my radar.

I only really started looking into it after a friend asked me what I thought about it. That question sent me down a short research rabbit hole, and what caught my attention wasn’t the antioxidant angle or the more speculative cognitive discussions. It was the mucolytic effect.

With my chronic sinusitis and persistent sinus congestion, thick mucus has basically been part of my normal for years. When I saw that NAC is used clinically as a mucolytic, helping thin mucus and improve clearance, I was intrigued. That’s not a flashy benefit, but it’s a very practical one if you’re someone who feels chronically blocked up.

I started taking it about a month ago.

So far, I will say it’s made a noticeable difference. My sinuses feel like they flow more easily rather than staying constantly congested, especially at night. Sleeping with clear airways is a different experience than sleeping with constant pressure and blockage. It’s not perfect, but it’s improved enough that I’m planning to stick with it for now.

If it also helps reduce airway inflammation more broadly, that’s a bonus. Between chronic sinusitis and environmental allergies, anything that supports airway health without heavy medication is worth testing, provided it’s done responsibly.

At the moment, I take one 1,000 mg capsule daily, in the morning with my other medications and supplements. Keeping it in the same routine as everything else makes it far more likely that I’ll stay consistent, and consistency is what actually determines whether something is worth keeping in.

Supplements I Don’t Use (And Why I’m Not A Fan)

For every supplement I take, there are a handful I pretty consistently avoid, and I’ll be blunt here… it’s not because I’m trying to be contrarian. It’s because most of them are either a waste of money, a distraction from the fundamentals, or they carry downsides that don’t justify the upside for the average person.

I’m also going to separate two ideas that often get mashed together:

“I don’t use this”

“I don’t advise most people to use this”

Sometimes those overlap. Sometimes they don’t. But with the categories below, I’m generally in the “hard pass” camp for most people.

Pre-Workout Supplements

Most pre-workouts are basically stimulants with better branding.

Yes, there are a few ingredients with some evidence behind them, but the reality is that the felt effect most people are chasing is caffeine (often paired with other stimulants), plus the buzz of tingles, pumps, and a sense that you’ve switched into “beast mode”.

If you like caffeine and you tolerate it well, you can get the useful part of that equation for a fraction of the price with coffee or a simple caffeine tablet, without the mystery blend and without accidentally taking a dose that trashes your sleep later.

And that’s the bigger issue. Sleep is still the most underrated performance enhancer available, and a lot of people are taking pre-workout because they’re chronically under-slept, under-recovered, and under-fuelled. In that situation, pre-workout isn’t “performance nutrition”. It’s a band-aid.

If someone genuinely needs a short-term boost for an occasional early session, fine. But for most people, regular pre-workout use becomes a dependency loop: poor sleep leads to stimulant use, stimulant use leads to poorer sleep, and the cycle keeps going. That’s not a stack. That’s a trap.

BCAAs

BCAAs are one of the most successful marketing stories in the supplement industry.

They’re not inherently harmful. They’re just unnecessary for most people, especially if you’re already consuming adequate protein.

BCAAs are three amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, valine). They can support signalling for muscle protein synthesis, but you still need the full set of essential amino acids, plus total protein, to actually build and repair muscle tissue. In practice, if you want the muscle and recovery benefits people think they’re buying with BCAAs, you’re better off spending that money on complete protein, either from food or from a protein powder you’ll actually use consistently.

There are niche cases where someone might use EAAs or BCAAs in a very specific context, but for 99% of people reading this, it’s just not a good investment.

Fat Burners

Fat burners are another category where the label and the reality don’t match.

Most of them are stimulants. Some add ingredients that slightly raise heart rate, slightly increase thermogenesis, slightly reduce perceived appetite, or make you sweat more. None of that is the same thing as meaningful fat loss.

If a fat burner “works,” it’s typically by:

Making you less hungry (and therefore you eat less), or

Giving you a stimulant hit (and therefore you feel more energetic), or

Acting as a mild diuretic (and therefore you drop water weight and think it’s fat)

There’s also the downside. Stimulant-based products can increase anxiety, disrupt sleep, raise blood pressure, and generally make people feel wired. Even if you feel good on them, the longer-term cost often shows up in sleep quality and recovery, and those are the two levers that keep fat loss and body composition moving in the right direction.

In my experience, fat burners are also psychologically unhelpful. They keep people looking for “something extra” instead of building the habits that actually make the difference.

Electrolyte Drinks or Pills

This one tends to surprise people, because electrolytes are important… but the way they’re marketed makes it sound like you need them every time you break a sweat.

For most people doing normal workouts, eating normal meals, and hydrating reasonably well, electrolyte supplements are unnecessary. You get sodium, potassium, magnesium, and other minerals through food, and your body is pretty good at regulating these systems unless you’re doing something extreme.

Where electrolytes might be useful is in very long endurance events, very hot conditions, heavy sweaters, or cases where someone is truly struggling with cramping or performance decline over prolonged efforts. Even then, it’s not a guarantee. Cramping is complex, and electrolyte replacement is only one possible piece of it.

If you’re training for a marathon, an ultra, or a long day in the mountains, electrolytes might be a practical tool to test. But if you’re doing a 45-minute lift or a 5K run, it’s usually not the missing piece.

For most people, electrolyte products are just expensive flavoured water with a health halo.

Flax, ALA, And “Plant-Based Omega-3s” (with one exception)

This one deserves a quick mention, because it’s a common point of confusion.

Flax seed, flax oil, and many plant-based omega-3 supplements provide ALA (alpha-linolenic acid). The issue is that ALA is not the same thing as EPA and DHA, which are the forms of omega-3 your body actually uses in meaningful amounts for cardiovascular, neurological, and anti-inflammatory effects.

Your body can convert ALA into EPA and DHA… but very poorly.

Conversion rates are often less than 10% for EPA, and even lower for DHA. In some cases, DHA conversion can be closer to 1–5%. That means you can be taking in what looks like a decent dose of “omega-3” on the label and still not meaningfully move your EPA and DHA levels.

For that reason, I generally consider flax oil and ALA-based omega-3 supplements a poor investment if your goal is to meaningfully improve omega-3 status. They’re not harmful. They’re just inefficient.

If someone wants a plant-based option, the only form I would actually recommend is algae oil, which directly provides EPA and DHA without relying on conversion from ALA. Something like NutraVege is a good example.

It’s typically less potent in EPA compared to high-dose fish oil, often around 50% as potent, but it’s usually about 80% as potent for DHA. That makes it dramatically more effective than ALA-based options and a completely reasonable alternative for vegetarians, vegans, or anyone who prefers to avoid fish oil.

If you’re going to spend money on omega-3 supplementation, it makes sense to use a form your body can actually use.

The Same “Why” Behind Every Diet That Works

If there’s one theme that runs through this whole supplements conversation, it’s this: nothing here is doing the heavy lifting.

Supplements can be helpful, but they’re a rounding error compared to consistent training, a sensible diet you can repeat, enough protein to actually support your body, and a calorie intake that matches your goal. If you’re not clear on that last part, it’s really easy to get pulled into “optimising” everything except the thing that matters most.

That’s why I built How Weight Loss Really Works.

It’s a short, free mini-course that explains the fundamentals of fat loss in plain language, without the hype, without the extremes, and without the weird diet rules people get stuck in. It’s designed to help you understand what’s actually driving progress, so you can make better decisions about food, training, and yes, whether any supplements are even worth your attention.

You can learn more about the course here:

https://www.jpsiou.com/how-weight-loss-really-works

Or if you want to get started right away, you can enrol directly here.

Further Reading

If you want to go deeper, here are the research links and reference pages used in creating this article:

Protein

Creatine

Omega-3 (Fish Oil, EPA/DHA)

Vitamin D

Vitamin K2

Vitamin C

ZMA (Zinc, Magnesium, B6)

NAC

Antioxidants In General